Building Futures in High-Demand Fields

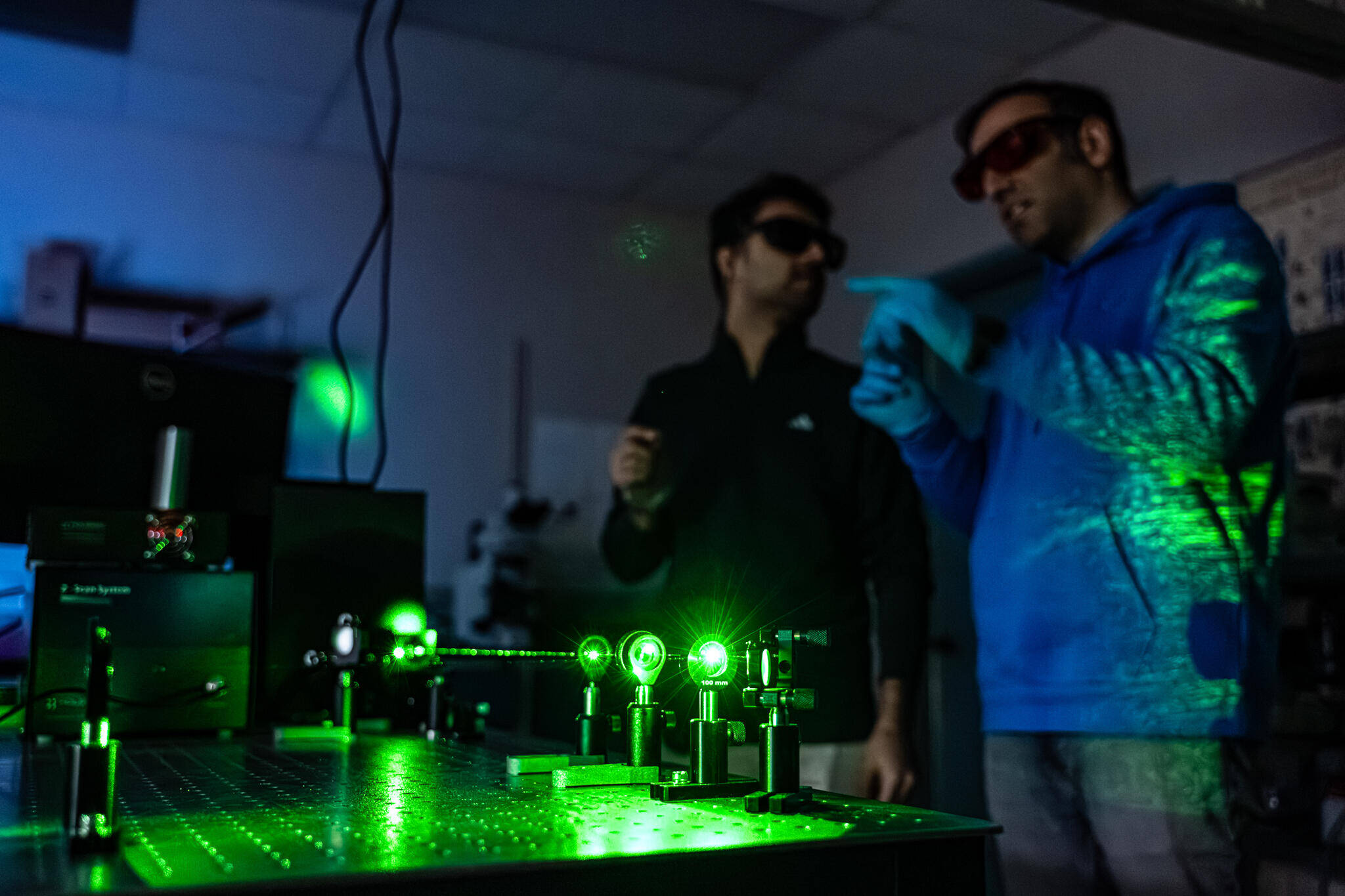

UIC student Hessam Shahbazi and Mohsen Bagheri Tabar operate a laser in the quantum optics lab at UIC, observing a chemical compound at a microscopic level. Photo by Yingtang Lu BDes ’20

When Hessam Shahbazi looks toward his future, he sees quantum computing — a field so revolutionary, it promises to reshape industries from aerospace to cybersecurity. As a PhD student in mechanical engineering at UIC, Shahbazi knows he’s in the right place at the right time.

Chicago has emerged as a national hub for quantum innovation, home to pioneers like Fermilab and Argonne National Laboratory and startups such as PsiQuantum and EeroQ Quantum Hardware. For Shahbazi and his peers, that proximity isn’t just geography, it’s opportunity.

“Being adjacent to all of these national labs and startups and companies, we have a better opportunity to build connections,” Shahbazi says.

Across its colleges, labs, clinics and institutes, UIC is preparing students to lead in industries that are either brand-new or undergoing dramatic reinvention. Nearly half of these students are first-generation, and 56% are Pell Grant-eligible, a powerful reminder that innovation thrives when opportunity is broad and inclusive. At the same time, UIC’s clinics and hospital deliver care to the most underserved communities in Chicago and across Illinois, reflecting the institution’s long-standing mission to provide the broadest access to the highest levels of educational, research and clinical excellence.

That mission is driving possibilities far beyond quantum. From nurse-led mobile health care to sustainability-driven chemical engineering, UIC is connecting a uniquely diverse, driven student body with front-door access to fields that are transforming the world.

by Steve Hendershot

UIC College of Nursing’s Mobile Health Unit vehicle at a rural community. Photo by Joshua Clark BFA ’08

“We’re working together for the common shared vision of taking care of a patient in rural America, or inner-city America and setting up the system for success”

— Carolyn Dickens, Associate Dean for Faculty Practice and Partnerships

Nurses Answer an Urgent Need for Rural Health Care

How do you deliver care to people far from major health centers? You take it on the road.

That’s what UIC nurse practitioner student Madison Wilson does aboard the Mobile Health & Wellness Services unit, a 38-foot rolling clinic operated by UIC College of Nursing and UI Health in rural communities near Peoria and in Chicago. Funded by a $3.1 million grant from the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration, the unit carries teams of health professionals, led by family nurse practitioner Summer Park , directly to residents.

The need is urgent. Health care in the U.S. is increasingly concentrated in large urban systems, leaving rural areas with fewer options. Between 2005 and present, 87 rural hospitals closed completely and another 65 stopped providing in-patient services, according to the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research at the University of North Carolina. Rural communities average just 30 physicians per 100,000 people — compared to 263 in urban areas — and that supply is projected to shrink another 23% by 2030.

UIC College of Nursing and UI Health are meeting this challenge by training nursing and nurse practitioner students to serve in their own rural communities, expanding access to care for those who need it most. For Wilson, a Peoria nurse and third-year graduate student, a combination of online coursework and earning clinical hours in the mobile unit made it possible to pursue her (DNP) degree while staying in her community. It also reshaped her career goals: “It’s extremely humbling, rewarding and meaningful to provide care that genuinely makes a difference, especially to people who might otherwise go without,” Wilson says.

The 38-foot Mobile Health Unit looks a bit like a rock band’s tour bus, and represents such an industry paradigm shift that Carolyn Dickens, clinical assistant professor and associate dean for faculty practice and partnerships at UIC College of Nursing, calls it “the future of health care.”

Area residents whose needs range from diabetes and hypertension management to getting a health care professional’s sign-off on a kid’s school sports physical are able to do so without having to schedule a road trip.

The mobile clinic is made possible in part because of an Illinois law that provides for primary care to be delivered by nurse practitioners, rather than requiring a physician’s oversight — a policy that could pave the way for expanded health care capacity in outlying areas. Nursing students aboard the mobile health unit work under the nurse practitioners, as do medical students training to become physicians.

“You’re working together for the common shared vision of taking care of a patient in rural America, or inner-city America. You’re setting up the system for success,” says Dickens.

Anagha Karnik BS ’25 poses alongside an art installation at McDonald’s Corporate Office in Chicago’s West Loop. Photo by Anthony Jackson

Companies are increasingly embracing the idea that digital innovation requires excellence in both technical skill and also design. Great code turns ideas into products; great design makes those products intuitive and useful. Yet technologists and creatives often speak different languages, and traditional education reinforces the divide. At UIC, for example, designers study in the College of Architecture, Design and the Arts (CADA), while computer scientists head to the College of Engineering — a common setup nationwide.

UIC’s new program bridges that gap. Students take 10 computer science courses and eight design courses, including studio work culminating in an integrative project focused on crossover applications like live coding or virtual reality. They also complete a year-long professional practice in interdisciplinary product development. Plans include a capstone co-taught by faculty from both colleges.

“This program is built on a very strong foundation,” says Pedro Neves, clinical assistant professor and faculty lead. “We have 50-plus years of computer science and design expertise at UIC, which makes it unique compared to other programs.”

The first full class of about 15 students will graduate in spring 2026, and hundreds have applied. Companies like Nike and Microsoft are already recruiting interns and graduates. Neves says the program’s appeal lies in its breadth: students learn to be “capital-D designers and capital-E engineers,” not just UX specialists or game developers. The goal is to produce innovators who can bridge disciplines and unlock new possibilities.

“The ideal is that students leave ready to build those bridges,” Neves says.

Anagha Karnik grew up loving engineering and the arts, too, but saw no way to combine both — until she discovered UIC’s groundbreaking computer science and design program, the first in the nation to offer an undergraduate degree in both disciplines. Three years later, Karnik became one of its first graduates and now works as a software engineer at McDonald’s.

UIC Combines Technical Skill and Design in Digital Innovation

The growing emphasis on education comes at a pivotal moment for health care. The industry has become increasingly consolidated and complex — more than 2,000 hospital mergers occurred between 1992 and 2023, and the share of physicians affiliated with health systems jumped from 29% to 41% in the past decade. In this environment, doctors need more than clinical expertise. They must also develop executive leadership skills and oversee medical research and programs that train residents to become skilled and reliable practitioners.

UIC’s MHPE equips physicians to do exactly that. Designed for doctors who want to teach and lead, the program combines medical education with leadership training. “It’s like an MBA for physicians who want to go into administration,” says Dr. Yoon Soo Park, department head and Ilene B. Harris Endowed Professor of Medical Education. “Physicians know how to care for patients, but when it comes to leadership, research or the science of teaching, those are skill sets they can build.”

UIC’s program remains one of few housed within a dedicated medical education department and is one of relatively few public schools to offer the degree. It was also among the first MHPE programs to offer online coursework, a key consideration since most students are practicing physicians, dentists or pharmacists when they enroll. Johnston, for example, is a resident in general surgery at Dartmouth Health in New Hampshire.

Park cherishes the opportunity to elevate the role medical education in the new era of large, consolidated health systems, in part because education has not traditionally received the focus it deserves within clinical settings.

“The argument that we’ve made is that if you invest in education, you’re actually going to get better patient outcomes,” Park says.

College of Medicine students practicing on a manikin in a simulation lab on campus.

When Tawni Johnston entered medical school, she imagined a future in surgery. A mentor named Brigitte Smith MHPE ’20 helped her discover another calling: training doctors to become great surgeons. That path led Johnston to UIC’s Master of Health Professions Education (MHPE), a degree designed to prepare physicians not just to teach, but to lead.

Through surgical education research, “I felt like I could really make a difference,” says Johnston.

At UIC, training doctors to teach other doctors has been an emphasis since 1959, when it founded its pioneering Department of Medical Education, housed within the College of Medicine. In 1968, the college introduced the MHPE program. In recent years, this niche degree has exploded in popularity — from seven offered worldwide in 1996 to 159 in 2019, according to a 2023 paper published in the journal Medical Teacher and coauthored by three UIC scholars. That’s due in part to changing recommendations from health care accrediting bodies, some of which now list the MHPE as a preferred credential for doctors overseeing education and residency programs in medical schools and hospitals.

Training Doctors To Meet Modern Leadership Challenges

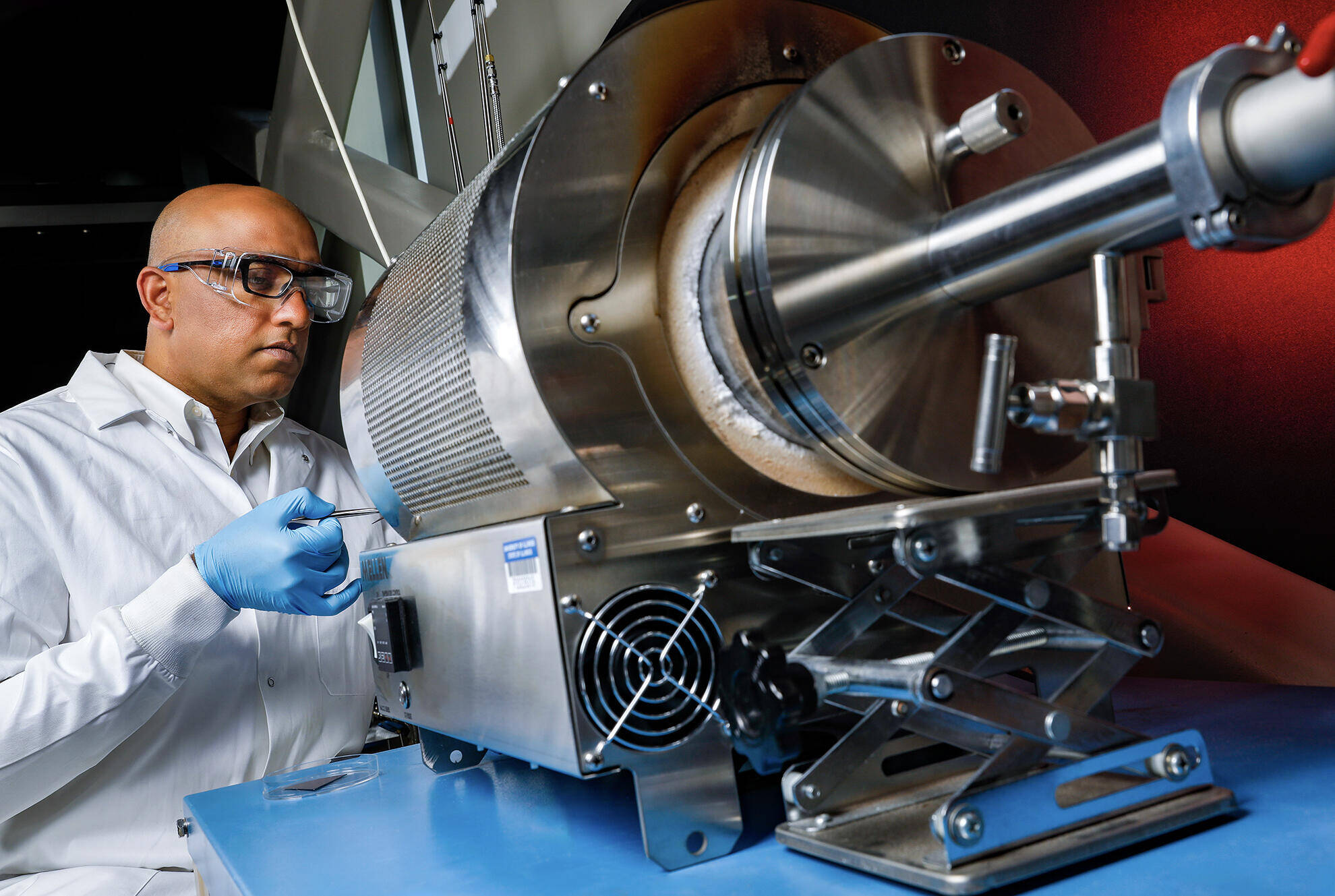

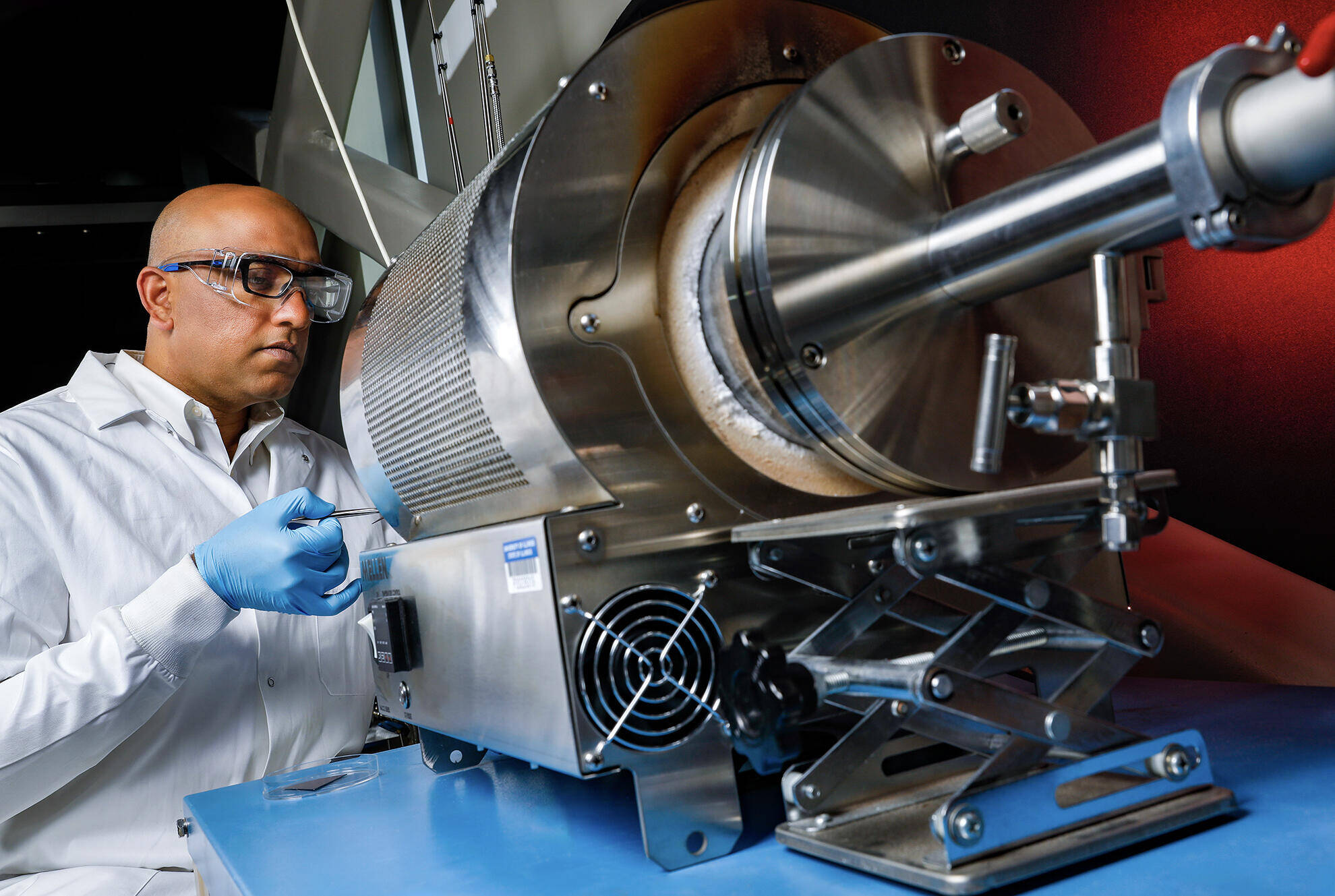

Vikas Berry, Dr. Satish C. & Asha Saxena Professor and Department Head in the Department of Chemical Engineering, operates a chemical vapor deposition system that can be used in the development of sustainable materials for next-generation technologies.

“When the world needed energy, chemical engineers provided solutions. Now we have abundant energy, but it’s coming from finite sources.... We have to use renewable resources, and chemical engineers can...get the job done.”

— Vikas Berry, Professor, Department of Chemical Engineering

“Chemical engineering is sustainability.” That mantra drives UIC’s Department of Chemical Engineering, led by Professor Vikas Berry. The field once synonymous with oil and plastics is now tackling climate challenges head-on, and UIC students are at the center of that transformation.

Chemical engineers have always solved society’s biggest problems, Berry says. “When the world needed energy, chemical engineers provided solutions. Now we have abundant energy, but it’s coming from finite sources. So we know that we have to use renewable resources, and chemical engineers can design catalysts and systems to get the job done.”

UIC faculty are pioneering water treatment technologies, including remediation of PFAS microplastics and leading Great Lakes ReNEW — a $160 million National Science Foundation-funded clean water initiative. Other researchers are developing next-generation batteries based on lithium-sulfur, lithium-carbon dioxide and sodium ion, as well as thermal batteries that charge using hot and cold air, removing electricity from the equation entirely. Still others are using AI to design catalysts that capture carbon dioxide using sunlight and convert it into useful materials.

Industry partnerships with companies like AbbVie, BP, 3M and Beyond Meat give students hands-on experience solving real-world problems. UIC’s Climate Engineering for Global Warming course introduces technologies that mitigate climate change and includes a field trip to a carbon capture facility. Berry says many students — often first-generation and Pell Grant recipients — are drawn to chemical engineering because they want to influence the environment, not just study it.

“They see other environmental-adjacent fields and conclude, ‘They’re studying the environment, but they’re not influencing it. I want to change it,’” Berry says. “Chemical engineering is positioned in a very unique way in which it has all of the skill sets that are required.”

Chemical Engineering Meets Sustainability

Hessam Shahbazi (left), Mohsen Bagheri Tabar (right) and a UIC student, Kalib McEuen (middle), sitting in front of a control unit at the UIC quantum optics lab. Photo by Anthony Jackson

That’s exactly what Hessam Shahbazi envisioned at the start: being in the right place at the right time. For him, that means quantum innovation. For Madison Wilson, it means transforming rural health care. For Anagha Karnik, it means bridging design and technology. For Tawni Johnston, it means shaping the next generation of surgeons through medical education leadership. For UIC chemical engineering students, it means leading the charge toward sustainability. Across every discipline, UIC is doing more than preparing students for jobs — it’s launching them into careers that will shape the future.

UIC’s quantum computing program celebrated a milestone in May when Ashley Blackwell became the first UIC student to earn a doctoral degree focused on quantum information science. Another graduate student will follow with a master’s degree later this year, and undergraduate opportunities are expanding fast. This fall, UIC debuted courses in quantum error correction, quantum hardware and sensing and quantum optics — with plans for a quantum entrepreneurship class on the horizon.

Students began catching the quantum bug even before formal coursework launched. Caleb Williams, who started as an electrical engineering major, co-founded a quantum student group and worked on a project at EeroQ, building a system that couples with the company’s superconducting qubit — the basic building block of quantum computing. For faculty member Zizwe Chase, that project exemplifies UIC’s approach: hands-on access to cutting-edge technology, interdisciplinary teamwork and exposure to quantum entrepreneurship.

“These students are very hungry to achieve and accomplish great things,” Chase says. “We want to show our students what’s possible — you can create your own pathway.”

Futures in Quantum

UIC student Hessam Shahbazi and Mohsen Bagheri Tabar operate a laser in the quantum optics lab at UIC, observing a chemical compound at a microscopic level. Photo by Yingtang Lu BDes ’20

Building Futures in High-Demand Fields

When Hessam Shahbazi looks toward his future, he sees quantum computing — a field so revolutionary, it promises to reshape industries from aerospace to cybersecurity. As a PhD student in mechanical engineering at UIC, Shahbazi knows he’s in the right place at the right time.

Chicago has emerged as a national hub for quantum innovation, home to pioneers like Fermilab and Argonne National Laboratory and startups such as PsiQuantum and EeroQ Quantum Hardware. For Shahbazi and his peers, that proximity isn’t just geography, it’s opportunity.

“Being adjacent to all of these national labs and startups and companies, we have a better opportunity to build connections,” Shahbazi says.

Across its colleges, labs, clinics and institutes, UIC is preparing students to lead in industries that are either brand-new or undergoing dramatic reinvention. Nearly half of these students are first-generation, and 56% are Pell Grant-eligible, a powerful reminder that innovation thrives when opportunity is broad and inclusive. At the same time, UIC’s clinics and hospital deliver care to the most underserved communities in Chicago and across Illinois, reflecting the institution’s long-standing mission to provide the broadest access to the highest levels of educational, research and clinical excellence.

That mission is driving possibilities far beyond quantum. From nurse-led mobile health care to sustainability-driven chemical engineering, UIC is connecting a uniquely diverse, driven student body with front-door access to fields that are transforming the world.

by Steve Hendershot

The 38-foot Mobile Health Unit looks a bit like a rock band’s tour bus, and represents such an industry paradigm shift that Carolyn Dickens, clinical assistant professor and associate dean for faculty practice and partnerships at UIC College of Nursing, calls it “the future of health care.”

Area residents whose needs range from diabetes and hypertension management to getting a health care professional’s sign-off on a kid’s school sports physical are able to do so without having to schedule a road trip.

The mobile clinic is made possible in part because of an Illinois law that provides for primary care to be delivered by nurse practitioners, rather than requiring a physician’s oversight — a policy that could pave the way for expanded health care capacity in outlying areas. Nursing students aboard the mobile health unit work under the nurse practitioners, as do medical students training to become physicians.

“You’re working together for the common shared vision of taking care of a patient in rural America, or inner-city America. You’re setting up the system for success,” says Dickens.

UIC College of Nursing’s Mobile Health Unit vehicle at a rural community. Photo by Joshua Clark BFA ’08

“We’re working together for the common shared vision of taking care of a patient in rural America, or inner-city America and setting up the system for success”

— Carolyn Dickens, Associate Dean for Faculty Practice and Partnerships

Nurses Answer an Urgent Need for Rural Health Care

How do you deliver care to people far from major health centers? You take it on the road.

That’s what UIC nurse practitioner student Madison Wilson does aboard the Mobile Health & Wellness Services unit, a 38-foot rolling clinic operated by UIC College of Nursing and UI Health in rural communities near Peoria and in Chicago. Funded by a $3.1 million grant from the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration, the unit carries teams of health professionals, led by family nurse practitioner Summer Park , directly to residents.

The need is urgent. Health care in the U.S. is increasingly concentrated in large urban systems, leaving rural areas with fewer options. Between 2005 and present, 87 rural hospitals closed completely and another 65 stopped providing in-patient services, according to the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research at the University of North Carolina. Rural communities average just 30 physicians per 100,000 people — compared to 263 in urban areas — and that supply is projected to shrink another 23% by 2030.

UIC College of Nursing and UI Health are meeting this challenge by training nursing and nurse practitioner students to serve in their own rural communities, expanding access to care for those who need it most. For Wilson, a Peoria nurse and third-year graduate student, a combination of online coursework and earning clinical hours in the mobile unit made it possible to pursue her (DNP) degree while staying in her community. It also reshaped her career goals: “It’s extremely humbling, rewarding and meaningful to provide care that genuinely makes a difference, especially to people who might otherwise go without,” Wilson says.

Companies are increasingly embracing the idea that digital innovation requires excellence in both technical skill and also design. Great code turns ideas into products; great design makes those products intuitive and useful. Yet technologists and creatives often speak different languages, and traditional education reinforces the divide. At UIC, for example, designers study in the College of Architecture, Design and the Arts (CADA), while computer scientists head to the College of Engineering — a common setup nationwide.

UIC’s new program bridges that gap. Students take 10 computer science courses and eight design courses, including studio work culminating in an integrative project focused on crossover applications like live coding or virtual reality. They also complete a year-long professional practice in interdisciplinary product development. Plans include a capstone co-taught by faculty from both colleges.

“This program is built on a very strong foundation,” says Pedro Neves, clinical assistant professor and faculty lead. “We have 50-plus years of computer science and design expertise at UIC, which makes it unique compared to other programs.”

The first full class of about 15 students will graduate in spring 2026, and hundreds have applied. Companies like Nike and Microsoft are already recruiting interns and graduates. Neves says the program’s appeal lies in its breadth: students learn to be “capital-D designers and capital-E engineers,” not just UX specialists or game developers. The goal is to produce innovators who can bridge disciplines and unlock new possibilities.

“The ideal is that students leave ready to build those bridges,” Neves says.

Anagha Karnik BS ’25 poses alongside an art installation at McDonald’s Corporate Office in Chicago’s West Loop. Photo by Anthony Jackson

Anagha Karnik grew up loving engineering and the arts, too, but saw no way to combine both — until she discovered UIC’s groundbreaking computer science and design program, the first in the nation to offer an undergraduate degree in both disciplines. Three years later, Karnik became one of its first graduates and now works as a software engineer at McDonald’s.

UIC Combines Technical Skill and Design in Digital Innovation

College of Medicine students practicing on a manikin in a simulation lab on campus.

The growing emphasis on education comes at a pivotal moment for health care. The industry has become increasingly consolidated and complex — more than 2,000 hospital mergers occurred between 1992 and 2023, and the share of physicians affiliated with health systems jumped from 29% to 41% in the past decade. In this environment, doctors need more than clinical expertise. They must also develop executive leadership skills and oversee medical research and programs that train residents to become skilled and reliable practitioners.

UIC’s MHPE equips physicians to do exactly that. Designed for doctors who want to teach and lead, the program combines medical education with leadership training. “It’s like an MBA for physicians who want to go into administration,” says Dr. Yoon Soo Park, department head and Ilene B. Harris Endowed Professor of Medical Education. “Physicians know how to care for patients, but when it comes to leadership, research or the science of teaching, those are skill sets they can build.”

UIC’s program remains one of few housed within a dedicated medical education department and is one of relatively few public schools to offer the degree. It was also among the first MHPE programs to offer online coursework, a key consideration since most students are practicing physicians, dentists or pharmacists when they enroll. Johnston, for example, is a resident in general surgery at Dartmouth Health in New Hampshire.

Park cherishes the opportunity to elevate the role medical education in the new era of large, consolidated health systems, in part because education has not traditionally received the focus it deserves within clinical settings.

“The argument that we’ve made is that if you invest in education, you’re actually going to get better patient outcomes,” Park says.

When Tawni Johnston entered medical school, she imagined a future in surgery. A mentor named Brigitte Smith MHPE ’20 helped her discover another calling: training doctors to become great surgeons. That path led Johnston to UIC’s Master of Health Professions Education (MHPE), a degree designed to prepare physicians not just to teach, but to lead.

Through surgical education research, “I felt like I could really make a difference,” says Johnston.

At UIC, training doctors to teach other doctors has been an emphasis since 1959, when it founded its pioneering Department of Medical Education, housed within the College of Medicine. In 1968, the college introduced the MHPE program. In recent years, this niche degree has exploded in popularity — from seven offered worldwide in 1996 to 159 in 2019, according to a 2023 paper published in the journal Medical Teacher and coauthored by three UIC scholars. That’s due in part to changing recommendations from health care accrediting bodies, some of which now list the MHPE as a preferred credential for doctors overseeing education and residency programs in medical schools and hospitals.

Training Doctors To Meet Modern Leadership Challenges

“When the world needed energy, chemical engineers provided solutions. Now we have abundant energy, but it’s coming from finite sources.... We have to use renewable resources, and chemical engineers can...get the job done.”

— Vikas Berry, Professor, Department of Chemical Engineering

Vikas Berry, Dr. Satish C. & Asha Saxena Professor and Department Head in the Department of Chemical Engineering, operates a chemical vapor deposition system that can be used in the development of sustainable materials for next-generation technologies.

“Chemical engineering is sustainability.” That mantra drives UIC’s Department of Chemical Engineering, led by Professor Vikas Berry. The field once synonymous with oil and plastics is now tackling climate challenges head-on, and UIC students are at the center of that transformation.

Chemical engineers have always solved society’s biggest problems, Berry says. “When the world needed energy, chemical engineers provided solutions. Now we have abundant energy, but it’s coming from finite sources. So we know that we have to use renewable resources, and chemical engineers can design catalysts and systems to get the job done.”

UIC faculty are pioneering water treatment technologies, including remediation of PFAS microplastics and leading Great Lakes ReNEW — a $160 million National Science Foundation-funded clean water initiative. Other researchers are developing next-generation batteries based on lithium-sulfur, lithium-carbon dioxide and sodium ion, as well as thermal batteries that charge using hot and cold air, removing electricity from the equation entirely. Still others are using AI to design catalysts that capture carbon dioxide using sunlight and convert it into useful materials.

Industry partnerships with companies like AbbVie, BP, 3M and Beyond Meat give students hands-on experience solving real-world problems. UIC’s Climate Engineering for Global Warming course introduces technologies that mitigate climate change and includes a field trip to a carbon capture facility. Berry says many students — often first-generation and Pell Grant recipients — are drawn to chemical engineering because they want to influence the environment, not just study it.

“They see other environmental-adjacent fields and conclude, ‘They’re studying the environment, but they’re not influencing it. I want to change it,’” Berry says. “Chemical engineering is positioned in a very unique way in which it has all of the skill sets that are required.”

Chemical Engineering Meets Sustainability

That’s exactly what Hessam Shahbazi envisioned at the start: being in the right place at the right time. For him, that means quantum innovation. For Madison Wilson, it means transforming rural health care. For Anagha Karnik, it means bridging design and technology. For Tawni Johnston, it means shaping the next generation of surgeons through medical education leadership. For UIC chemical engineering students, it means leading the charge toward sustainability. Across every discipline, UIC is doing more than preparing students for jobs — it’s launching them into careers that will shape the future.

Hessam Shahbazi (left), Mohsen Bagheri Tabar (right) and a UIC student, Kalib McEuen (middle), sitting in front of a control unit at the UIC quantum optics lab. Photo by Anthony Jackson

UIC’s quantum computing program celebrated a milestone in May when Ashley Blackwell became the first UIC student to earn a doctoral degree focused on quantum information science. Another graduate student will follow with a master’s degree later this year, and undergraduate opportunities are expanding fast. This fall, UIC debuted courses in quantum error correction, quantum hardware and sensing and quantum optics — with plans for a quantum entrepreneurship class on the horizon.

Students began catching the quantum bug even before formal coursework launched. Caleb Williams, who started as an electrical engineering major, co-founded a quantum student group and worked on a project at EeroQ, building a system that couples with the company’s superconducting qubit — the basic building block of quantum computing. For faculty member Zizwe Chase, that project exemplifies UIC’s approach: hands-on access to cutting-edge technology, interdisciplinary teamwork and exposure to quantum entrepreneurship.

“These students are very hungry to achieve and accomplish great things,” Chase says. “We want to show our students what’s possible — you can create your own pathway.”