Drug Discovery

for All

Video: Anthony Jackson

UIC researchers are partnering with community advocates to develop treatments to improve health outcomes for all populations.

By Cindy Kuzma

“He’s right there,” says Natalie Reizine, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Illinois Cancer Center, when asked what inspired her to become a prostate cancer researcher. She’s pointing to a photo of her father on a shelf across from her desk.

“I’ve been interested in oncology personally for a long time,” Reizine says. “My father was diagnosed with cancer when I was a teenager. My father and my patients are what drive me.”

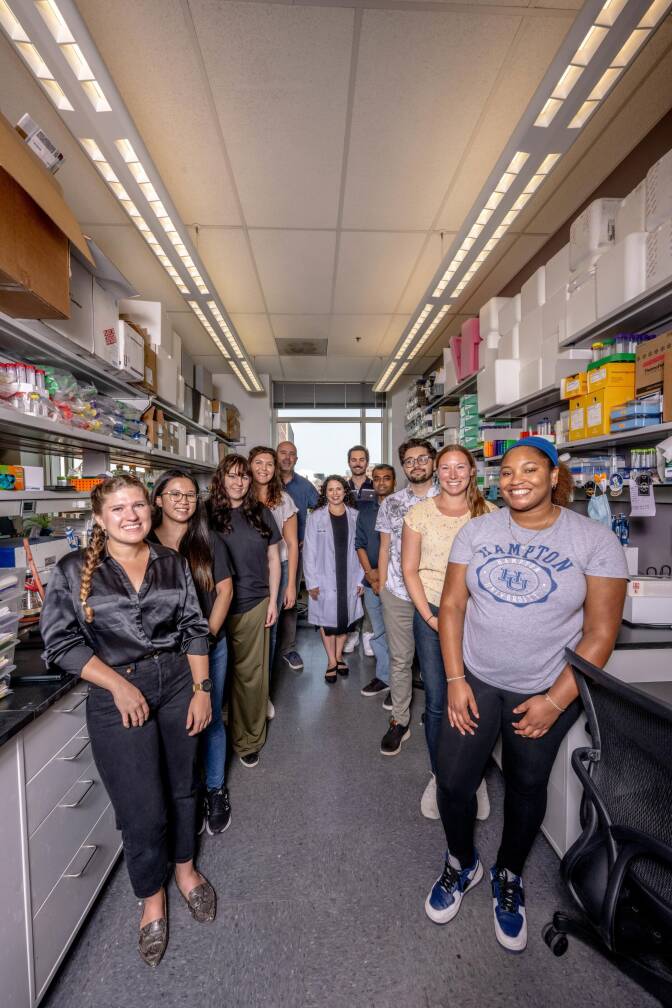

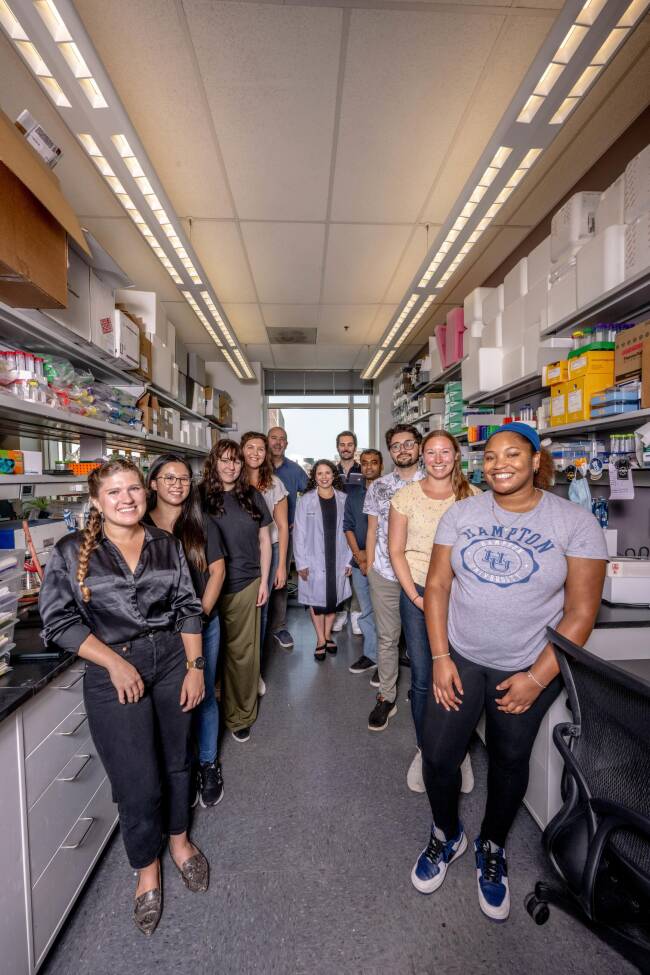

Dr. Natalie Reizine, center, accompanied by Dr. Donald Vander Griend, PhD, and student researchers in the Vander Griend laboratory.

If you are willing to bring research into the community, you can do a lot of good in breaking the previous distrust by showing you’re willing to take on questions and doubt and build relationships.

— Charles Walton, community advisory board member

Like most Cancer Center patients, Reizine’s come primarily from underserved areas of Chicago and from racial and ethnic groups that have previously been excluded and mistreated by researchers. So for her upcoming study on the effectiveness of licorice root for treating prostate cancer, Reizine formed an advisory board of three Black business leaders and community organizers to collaborate on the study design and help build trust among the men most likely to benefit from treatment.

“I’ve been involved in efforts to help bridge the gap between the community and the Cancer Center and get them out into the community,” says Charles Walton, who holds a seat on both Reizine’s advisory board and the Cancer Center’s advisory board and is the former executive director and current consultant to 100 Black Men of Chicago. “If you are willing to bring research into the community, you can do a lot of good in breaking the previous distrust by showing you’re willing take on questions and doubt and build relationships.”

It’s a sentiment echoed by advisory board member Melvin Thompson, who previously served as executive director of the Endeleo Institute, a community-centered organization for underserved populations. “In this line of work, you have to listen,” he says. “Sometimes people will vent, and that’s necessary because they haven’t been heard.”

Reizine’s team has given presentations at community health fairs and plans to hold a lab mixer where community members are invited into the laboratory of Donald Vander Griend, associate professor in the department of pathology at UIC, where Reizine mentors PhD students and has samples from her studies tested.

Community advisory boards are central to the Cancer Center’s research — especially when it comes to developing and testing drugs and treatments to cure diseases disproportionately impacting its diverse patient population. UIC has identified these as cancer, neurodegenerative and infectious diseases, and women’s health. It focuses its research and engagement in these areas.

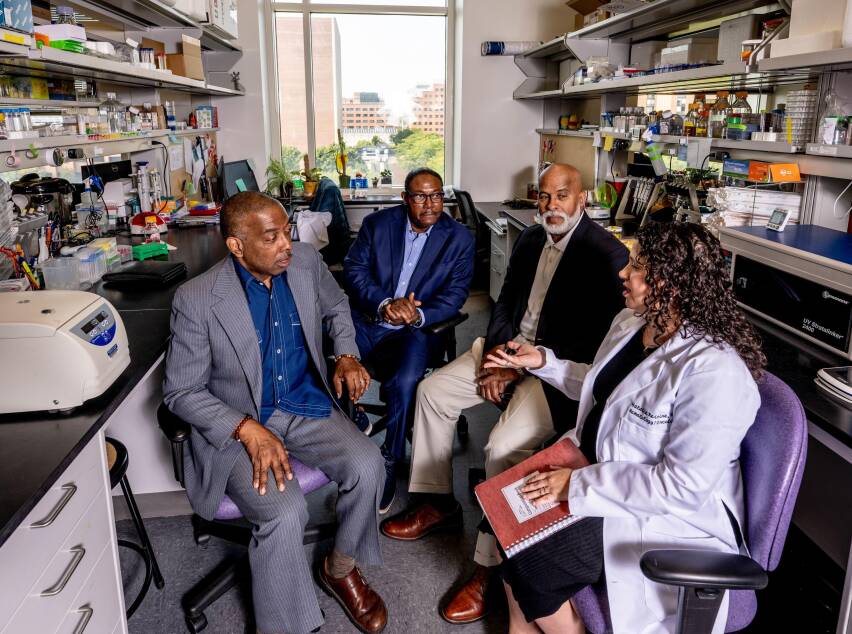

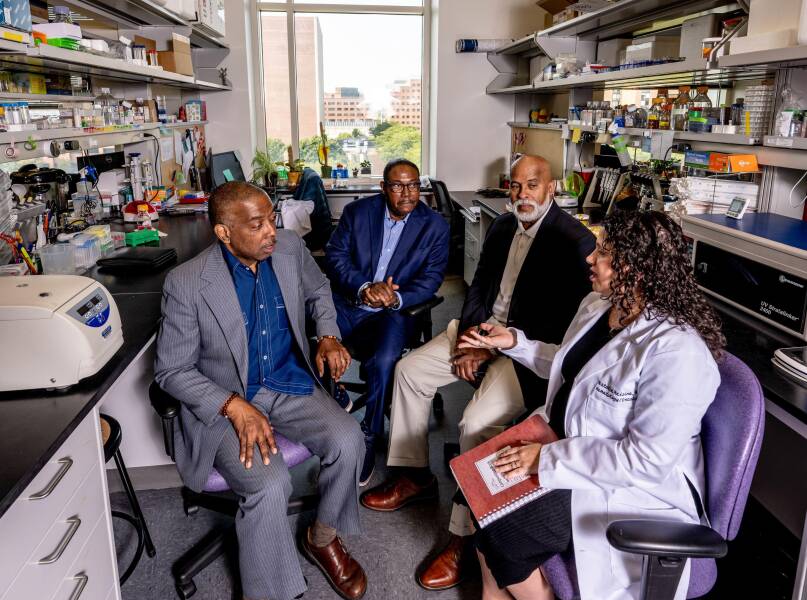

Dr. Natalie Reizine, right, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Illinois Cancer Center, discusses the work done at the Vander Griend Lab at UIC with members of her community advisory board, from left, Melvin Thompson, Elverage Allen and Charles Walton. Photo: Anthony Jackson

Educating patients about risks and detecting these diseases early is key to addressing health disparities and establishing equal health outcomes for all people. To do that, the Cancer Center’s Community Engagement and Health Equity Office fosters relationships with leaders who can open a two-way dialogue between communities and researchers who are addressing their needs.

“I liken it to being invited to a party by a stranger,” says Elverage Allen, an advisory board member, former advertising executive and co-host with his wife, Shay Allen, of “Prostate Cancer Real Talk,” a podcast with more than 1.4 million monthly listeners. “Are you more likely to go to a party a stranger invites you to or a friend?”

As a Black man and a prostate cancer survivor Allen is a credible messenger to engage Black communities in life-saving screening, trials and care.

The Future of Community-Engaged Drug Discovery

Health disparities occur due to a complex interplay between genetics and environment, says Jan Kitajewski, director of the University of Illinois Cancer Center and head of UIC’s Department of Physiology and Biophysics.

Illinois Department of Public Health statistics suggest, for example, that a Black woman in Chicago’s Englewood neighborhood is 40% more likely to die from breast cancer than a white woman living 10 miles north in Chicago’s Streeterville neighborhood.

People who are Black, as reported by the journal Health Affairs, and Hispanic, as reported by the National Library of Medicine, are more likely to be diagnosed with late-stage cancers. And, according to the Centers for Disease Control, infectious diseases such as influenza send disproportionately more people of color to the hospital. There are also global health threats like tuberculosis and malaria, which, the World Health Organization reports, proliferate in lower-income countries.

“There is science that can be advanced if you understand community needs better,” says Kitajewski.

The Cancer Center’s deep connections to local communities allow for this listening and inclusion and pursuit of its mission to eliminate cancer health inequities. It is also one of the reasons the Cancer Center accepted an invitation to apply for National Cancer Institute designation. If the designation is awarded, it will come with even more resources for addressing the needs of underserved communities.

The Cancer Center’s community engagement also positions it to catalyze drug research across the entire university. It is one of four partners in the Drug Discovery and Cancer Research Pavilion (DDCRP), an innovative building the university plans to construct to expedite new treatments for cancer, neurodegenerative and infectious diseases, and women’s health issues, all of which disproportionately affect underserved communities. Along with the Cancer Center, the DDCRP will house world-class researchers from the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences (LAS) Department of Chemistry, Herbert M. and Carol H. Retzky College of Pharmacy and UICentre, which supports drug discovery projects across UIC with seed grants, a dedicated staff of 10 PhD scientists and specialized equipment.

“Innovation, especially when it addresses medical disparities, usually comes from people like academics who explore different possibilities that aren’t tied to profit,” says LAS Science Endowed Chair and Distinguished Professor of Chemical Biology Wonhwa Cho. “Pharmaceutical companies are very good at making the final product and optimizing the process. We don’t do research to make money. We want to do work that matters.”

A Black woman in Chicago’s Englewood neighborhood is 40% more likely to die from breast cancer than a white woman living 10 miles north in Chicago’s Streeterville neighborhood.

— Illinois Department of Public Health

Infectious Disease

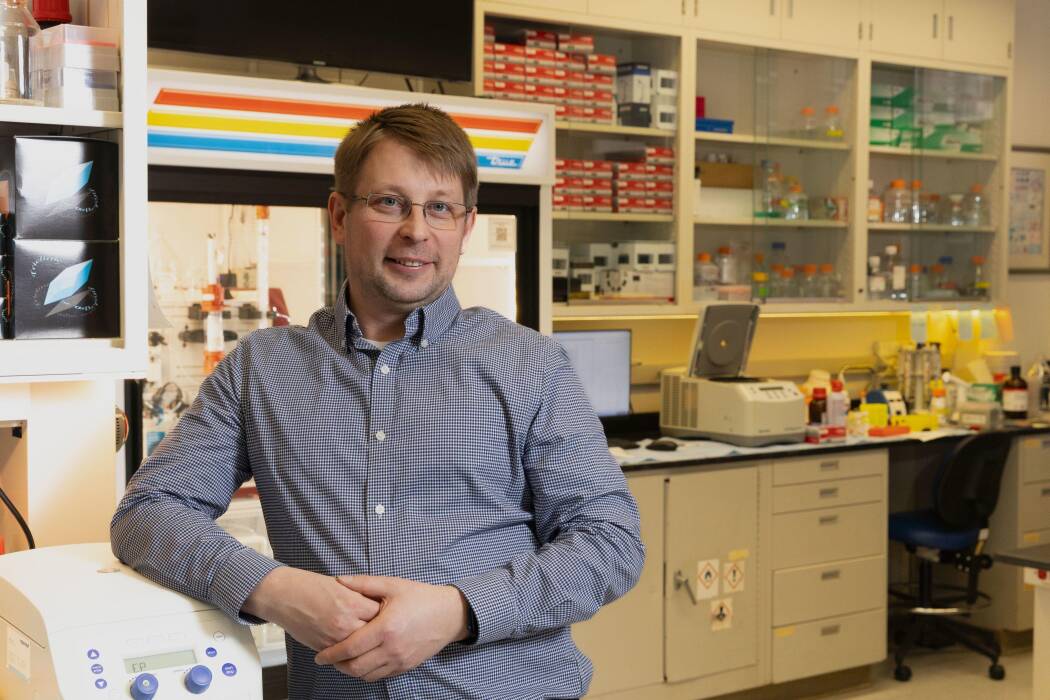

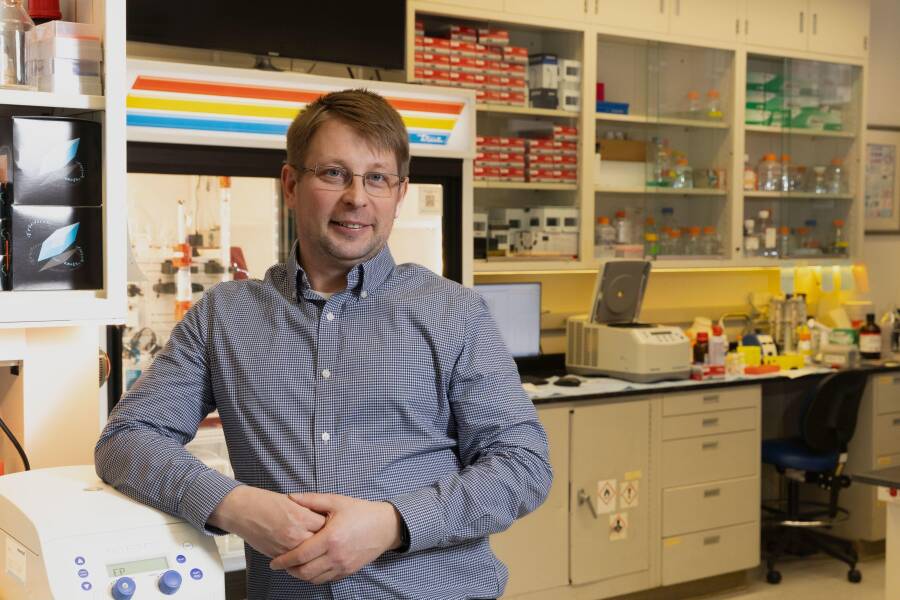

UIC’s Yury Polikanov, professor of Biological Sciences in LAS. Photo: Jenny Fontaine.

Infectious diseases caused by pathogenic bacteria are a threat to human health. Antibiotics have been successfully used for nearly 100 years to treat infectious diseases.

The incredible adaptability of bacterial cells causes the currently used antibiotics to become inactive and/or ineffective, creating a growing demand for newly designed drugs. According to the World Health Organization, drug-resistant bacteria kill nearly 1.3 million people each year.

Yury Polikanov, professor of Biological Sciences in LAS, sees hope.

He says these resistant bacterial strains develop quickly because some microbes in natural reservoirs already contain genes that make them resistant to antibacterials and it is only a question of time that these genes will get horizontally transferred.

The moment a new antibiotic is offered, the clock begins ticking — and the more it’s used, the sooner it becomes less effective. The goal is to create new drugs that are powerful against drug-resistant pathogens.

That’s why Polikanov’s research — and that of his colleagues, research professor Nora Vázquez-Laslop and distinguished professor Alexander Mankin, both in the Center for Biomolecular Sciences in the Retzky College of Pharmacy — is crucial. Both work on ways to attack bacterial cells’ ribosomes, molecular machines that work like 3D printers to produce proteins.

“Because the synthesis of proteins is crucial to life, if you stop it, the bacteria cannot live,” Polikanov says.

Human cells have ribosomes too, but they’re different enough from their bacterial counterparts that compounds can be developed to target bacterial ribosomes. This is a novel approach to crafting new antimicrobials academic researchers like Polikanov are free to pursue because they don’t have to consider the bottom line.

Along the way, they’re building a case for more investment in their approach. If they can provide ample evidence it works — and pinpoint specific compounds that will likely be effective — pharmaceutical companies will be more likely to step in and usher a new drug through FDA approval.

Cancer

The CDC reports people who are Black and Hispanic are more likely to be diagnosed with late-stage cancers, making treatment more challenging and increasing the risk of death. In fact, Black women are 40% more likely to die from breast cancer than white women.

Enter Professor Debra Tonetti. By the time she joined the Retzky College of Pharmacy in 2001, she was already working to solve a major problem in cancer treatment. About three-fourths of women with breast cancer have a type that responds effectively to endocrine therapy, usually with the drugs tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors.

But for nearly half of these patients, these endocrine drugs eventually stop working. Their cancer becomes metastatic, meaning it spreads to other parts of their body. At that point, physicians have few choices outside of toxic chemotherapy.

Tonetti aimed to understand why this happens. She created mouse models of treatment-resistant breast cancer, exploring what made these tumors tick and how to shrink them. Once she had some basic ideas — including that, though estrogen fueled their growth, some forms of the hormone could also work against these cancers — she began exploring how to turn those ideas into new cancer drugs.

The next step was a crucial one. Tonetti walked down the hall to the lab of a colleague, Greg Thatcher, then a fellow member of the Cancer Center and the founding director of UICentre.

“My expertise is cancer biology; his is in medicinal chemistry,” Tonetti says. “You don’t get a drug unless you have both pieces together.”

Based on Tonetti’s findings, Thatcher tweaked molecules to engineer a new compound, which they tested and ultimately submitted in an investigational new drug application to the Food and Drug Administration, which granted them approval to conduct a Phase I clinical trial.

In Phase I trials, which are designed primarily to test drug safety, not efficacy, the results were more compelling than they could have hoped. In seven of the 15 patients enrolled, their compound halted disease progression; in two of them, this stabilization period lasted 10 months.

“Hearing that their quality of life was turned around — that was very gratifying to see,” Tonetti says.

Meanwhile, in the chemistry department, Cho has spent a nearly 30-year career studying lipids. These fatty compounds, including cholesterol, were once thought to primarily form cell membranes. But thanks to the work of researchers like Cho, it’s now clear they serve a wide variety of functions, including mediating the way cells respond to each other and their environment.

While he was toiling away to determine exactly how lipids exert their effects, he and other cancer biologists recognized their crucial role in tumor development. So Cho found himself with an exciting and gratifying new direction for his work: developing life-saving treatments for cancer, a disease that will kill more than 600,000 Americans this year alone, with disproportionately more deaths among racial and ethnic minorities.

“Cancer uses many different tricks to survive and proliferate and metastasize, and many of these processes seem to critically depend on lipids,” he says. “If you block these lipid-mediated processes, you can suppress the growth of cancer cells, you can hinder their interaction with the immune system, you can block their way of developing resistance to drugs. You can basically eradicate cancer.”

Working with collaborators across UIC and beyond — including the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston — Cho and his lab have now identified several compounds that hold potential as cancer therapies, including potential drug candidates for colorectal cancer and inflammatory breast cancer.

The realization that his work could help dismantle health disparities — both inflammatory breast cancer and colorectal cancer are more common and more deadly among Black patients — has inspired Cho to continue forging ahead into brave new spaces.

The process of developing a new drug is long and arduous, but he and Tonetti are moving full steam ahead, building on UIC’s strong history in the field. Previous success stories include Prezista, a 2016-approved HIV drug discovered by researchers in the LAS’ Department of Chemistry that has helped transform the treatment of the disease; Shingrix, a shingles vaccine on the market since 2017 that originated in the College of Medicine; Tice BCG, a weakened live bacterium used to treat bladder cancer developed in the Retzky College of Pharmacy; and Phexxi, a nonhormonal contraceptive gel developed by faculty in the Retzky College of Pharmacy that the FDA approved in 2020.

The realization that his work could help dismantle health disparities — both inflammatory breast cancer and colorectal cancer are more common and more deadly among Black patients — has inspired Cho to continue forging ahead into brave new spaces.

— LAS Science Endowed Chair and Distinguished Professor of Chemical Biology Wonhwa Cho

Providing the Tools

Big ideas don’t become the pills or injections that change lives without cutting-edge technology and the coordination of the many steps necessary in drug development.

Fortunately, UIC offers support every step along the way, says Paul Carlier, Hans W. Vahlteich Chair in Medicinal Chemistry, professor of pharmaceutical sciences and chemistry, and the director of UICentre since 2022.

Once researchers like Tonetti or Cho identify a promising pathway, the next step is to determine if it’s possible to develop a drug that accomplishes what they hope. This stage is where tens or even hundreds of thousands of candidate molecules are tested to see if they might work.

From there, researchers might license the target drug to a pharmaceutical company, which UIC’s Office of Technology Management assists in. That company would then provide the significant resources required to advance the drug into clinical trials.

While those trials aren’t necessarily done at UIC, they can be — and in fact, many drug companies will bring compounds developed at other institutions here for testing due to the unique patient population. (In trials done through the Cancer Center, for example, 79% percent of the patients enrolled are Black or Hispanic.)

“UICentre is unique within Chicago with respect to the absolute scope and depth of drug discovery capabilities,” Carlier says. “Other institutions may offer pieces, but they don’t have the whole menu.”

Representation Matters

There are so many ways science can make better drugs by having diverse patients in clinical trials and an appreciation for all the features that make us different – our socioeconomic status, our nutrition, our genetics, our ability to get access to screenings and care.

— Jan Kitajewski, director of the University of Illinois Cancer Center and head of UIC’s Department of Physiology and Biophysics

To truly impact health disparities, drug discovery must not only listen to the needs of communities but also include diverse populations in trials.

Not doing this would mean some people are unnecessarily barred from potentially life-saving treatments, and trial results are skewed because they don’t include people who are more susceptible to aggressive forms of cancer, Kitajewski says.

Take, for example, the many Black people of sub-Saharan African descent who have a genetic variation that protects them from some types of malaria but also decreases levels of white blood cells called neutrophils. Because many cancer treatments also affect neutrophil levels, people with this variation, called the Duffy mutation, are often excluded from clinical trials.

Designing drugs that truly work for everyone is a moral imperative that demands an understanding of everything, from these genetic differences to how a person’s neighborhood influences their health.

“There are so many ways science can make better drugs by having diverse patients in clinical trials and an appreciation for all the features that make us different — our socioeconomic status, our nutrition, our genetics, our ability to get access to screenings and care,” says Kitajewski. “The science of the future will integrate all of those features to think about how patients should be best served.”

That’s where UIC truly shines. In addition to its underlying social justice mission and diverse faculty and student body, UIC’s community-to-bench model means input from patients and on-the-ground partnerships with community members shape both the direction of research and the implementation of its outcomes, says Lisa Freeman, dean of LAS.

The Retzky College of Pharmacy and College of Medicine house not only researchers working on the biological mechanisms of disease and the medicinal chemistry needed to develop drugs, but also clinicians working directly with patients.

“We have around 100 pharmacists who work in the clinics and the hospital, with physicians, helping treat patients with these medications,” says Glen Schumock, Herbert M. and Carol H. Retzky Dean of the College of Pharmacy. “They can see what’s not working with current drugs and give basic researchers ideas on how to better design the next generation of drugs. We can always provide feedback, in a kind of constant loop.”

Facilitating the Process

When Cho works with researchers from the College of Medicine or utilizes core facilities there, one of his lab members packs samples in dry ice and transports them across campus, about a mile trip. In the new DDCRP, with more collaborators under one roof, existing projects will move more quickly and smoothly.

Then, there are the serendipitous discoveries and partnerships that come from inhabiting the same space — that ability to do what Tonetti did years ago and stride down the hall to discuss a burning research question.

“When you bring people together who have different and complementary sets of expertise, the fact that you’re in the same building will lead to conversations that turn into ideas, which turn into projects that would have never happened had we continued to operate in our own separate spaces,” Carlier says.

That cross-pollination will also extend to community partners. Community members are involved at many levels in the Cancer Center and other research areas — they sit on advisory boards, review grants, weigh in on the design of clinical trials and contribute to advocacy work by joining faculty and staff to talk to state and national lawmakers.

“They do everything that we do short of putting on a lab coat and doing the experiments at the bench — and one day, maybe that will be part of what they do, too,” Kitajewski says.

Better Health for All

UIC’s mission is to provide the broadest access to the highest levels of educational, research and clinical excellence, an idea that resonates across the university, hospital and clinics.

For Reizine — and many others — treating patients and researching cures are not just a professional aspiration, they are deeply personal.

“Oncology is a hard field. I take care of metastatic patients, who ultimately succumb to their disease once we've run out of the therapies,” she says. “But what helps me is thinking of how these patients live on in the research and altruistically help others.”

It’s something that Allen, one of Reizine’s community advisory board members, noticed.

“When you talk to someone at the Cancer Center, you don’t feel like you’re talking to a scientist or doctor,” he says.

“You know you’re talking to a health care professional, but what you don’t expect is that personal commitment. You hear other people talking about doing things in the community, but here is an organization that’s actually doing it. That’s special.”

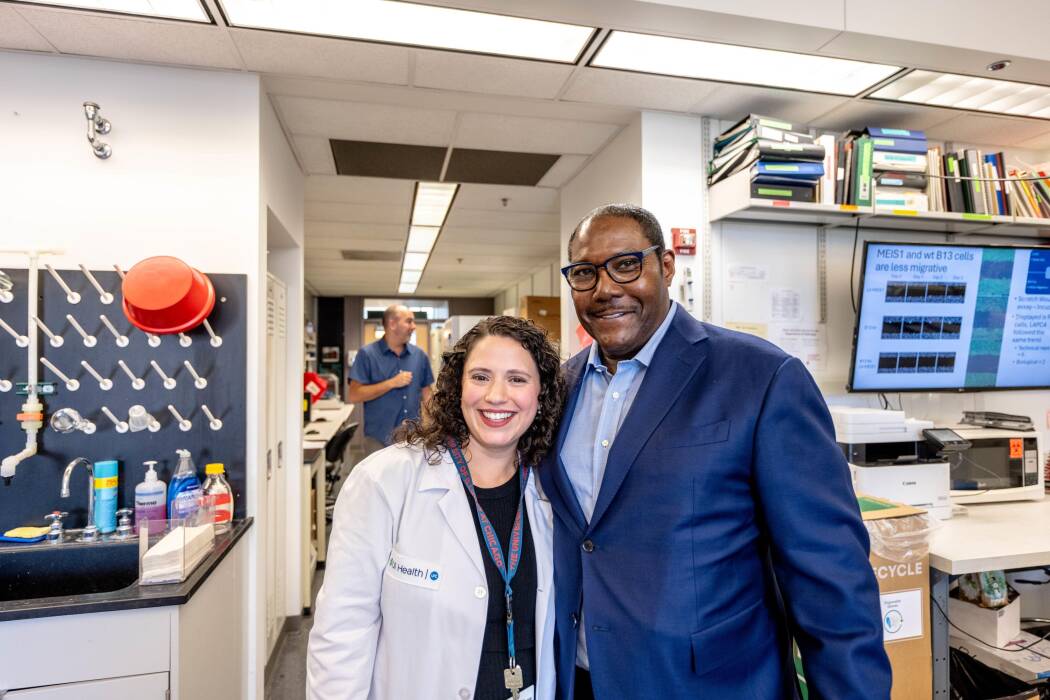

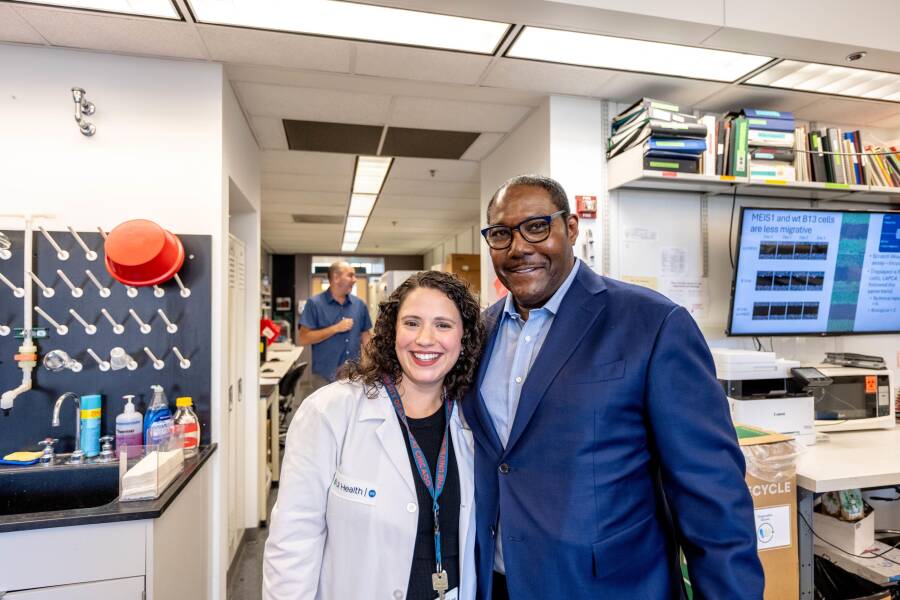

Dr. Natalie Reizine poses with Elverage Allen during his visit to the Vander Griend Lab at UIC. Reizine and Donald Vander Griend, associate professor in pathology and head of the prostate cancer laboratory, have both been guests on Allen’s podcast, “Prostate Cancer Real Talk.” Photo: Anthony Jackson

You can listen to Allen’s interviews with Reizine and Vander Griend on “Prostate Cancer Real Talk.”

Drug Discovery

for All

Video: Anthony Jackson

Like most Cancer Center patients, Reizine’s come primarily from underserved areas of Chicago and from racial and ethnic groups that have previously been excluded and mistreated by researchers. So for her upcoming study on the effectiveness of licorice root for treating prostate cancer, Reizine formed an advisory board of three Black business leaders and community organizers to collaborate on the study design and help build trust among the men most likely to benefit from treatment.

“I’ve been involved in efforts to help bridge the gap between the community and the Cancer Center and get them out into the community,” says Charles Walton, who holds a seat on both Reizine’s advisory board and the Cancer Center’s advisory board and is the former executive director and current consultant to 100 Black Men of Chicago. “If you are willing to bring research into the community, you can do a lot of good in breaking the previous distrust by showing you’re willing take on questions and doubt and build relationships.”

It’s a sentiment echoed by advisory board member Melvin Thompson, who previously served as executive director of the Endeleo Institute, a community-centered organization for underserved populations. “In this line of work, you have to listen,” he says. “Sometimes people will vent, and that’s necessary because they haven’t been heard.”

UIC researchers are partnering with community advocates to develop treatments to improve health outcomes for all populations.

By Cindy Kuzma

Dr. Natalie Reizine, right, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Illinois Cancer Center, discusses the work done at the Vander Griend Lab at UIC with members of her community advisory board, from left, Melvin Thompson, Elverage Allen and Charles Walton. Photo: Anthony Jackson

“He’s right there,” says Natalie Reizine, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Illinois Cancer Center, when asked what inspired her to become a prostate cancer researcher. She’s pointing to a photo of her father on a shelf across from her desk.

“I’ve been interested in oncology personally for a long time,” Reizine says. “My father was diagnosed with cancer when I was a teenager. My father and my patients are what drive me.”

Educating patients about risks and detecting these diseases early is key to addressing health disparities and establishing equal health outcomes for all people. To do that, the Cancer Center’s Community Engagement and Health Equity Office fosters relationships with leaders who can open a two-way dialogue between communities and researchers who are addressing their needs.

“I liken it to being invited to a party by a stranger,” says Elverage Allen, an advisory board member, former advertising executive and co-host with his wife, Shay Allen, of “Prostate Cancer Real Talk,” a podcast with more than 1.4 million monthly listeners. “Are you more likely to go to a party a stranger invites you to or a friend?”

As a Black man and a prostate cancer survivor Allen is a credible messenger to engage Black communities in life-saving screening, trials and care.

Dr. Natalie Reizine, center, accompanied by Dr. Donald Vander Griend, PhD, and student researchers in the Vander Griend laboratory.

If you are willing to bring research into the community, you can do a lot of good in breaking the previous distrust by showing you’re willing to take on questions and doubt and build relationships.

— Charles Walton,

community advisory board member

Reizine’s team has given presentations at community health fairs and plans to hold a lab mixer where community members are invited into the laboratory of Donald Vander Griend, associate professor in the department of pathology at UIC, where Reizine mentors PhD students and has samples from her studies tested.

Community advisory boards are central to the Cancer Center’s research — especially when it comes to developing and testing drugs and treatments to cure diseases disproportionately impacting its diverse patient population. UIC has identified these as cancer, neurodegenerative and infectious diseases, and women’s health. It focuses its research and engagement in these areas.

Health disparities occur due to a complex interplay between genetics and environment, says Jan Kitajewski, director of the University of Illinois Cancer Center and head of UIC’s Department of Physiology and Biophysics.

Illinois Department of Public Health statistics suggest, for example, that a Black woman in Chicago’s Englewood neighborhood is 40% more likely to die from breast cancer than a white woman living 10 miles north in Chicago’s Streeterville neighborhood.

People who are Black, as reported by the journal Health Affairs, and Hispanic, as reported by the National Library of Medicine, are more likely to be diagnosed with late-stage cancers. And, according to the Centers for Disease Control, infectious diseases such as influenza send disproportionately more people of color to the hospital. There are also global health threats like tuberculosis and malaria, which, the World Health Organization reports, proliferate in lower-income countries.

“There is science that can be advanced if you understand community needs better,” says Kitajewski.

The Future of Community-Engaged Drug Discovery

A Black woman in Chicago’s Englewood neighborhood is 40% more likely to die from breast cancer than a white woman living 10 miles north in Chicago’s Streeterville neighborhood.

— Illinois Department of Public Health

The Cancer Center’s deep connections to local communities allow for this listening and inclusion and pursuit of its mission to eliminate cancer health inequities. It is also one of the reasons the Cancer Center accepted an invitation to apply for National Cancer Institute designation. If the designation is awarded, it will come with even more resources for addressing the needs of underserved communities.

The Cancer Center’s community engagement also positions it to catalyze drug research across the entire university. It is one of four partners in the Drug Discovery and Cancer Research Pavilion (DDCRP), an innovative building the university plans to construct to expedite new treatments for cancer, neurodegenerative and infectious diseases and women’s health issues, all of which disproportionately affect underserved communities. Along with the Cancer Center, the DDCRP will house world-class researchers from the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences (LAS) Department of Chemistry, Herbert M. and Carol H. Retzky College of Pharmacy and UICentre, which supports drug discovery projects across UIC with seed grants, a dedicated staff of 10 PhD scientists and specialized equipment.

“Innovation, especially when it addresses medical disparities, usually comes from people like academics who explore different possibilities that aren’t tied to profit,” says LAS Science Endowed Chair and Distinguished Professor of Chemical Biology Wonhwa Cho. “Pharmaceutical companies are very good at making the final product and optimizing the process. We don’t do research to make money. We want to do work that matters.”

Infectious Disease

UIC’s Yury Polikanov, professor of Biological Sciences in LAS. Photo: Jenny Fontaine.

Infectious diseases caused by pathogenic bacteria are a threat to human health. Antibiotics Infectious diseases caused by pathogenic bacteria are a threat to human health. Antibiotics have been successfully used for nearly 100 years to treat infectious diseases.

The incredible adaptability of bacterial cells causes the currently used antibiotics to become inactive and/or ineffective, creating a growing demand for newly designed drugs. According to the World Health Organization, drug-resistant bacteria kill nearly 1.3 million people each year. been successfully used for nearly 100 years to treat infectious diseases.

Yury Polikanov, professor of Biological Sciences in LAS, sees hope.

He says these resistant bacterial strains develop quickly because some microbes in natural reservoirs already contain genes that make them resistant to antibacterials and it is only a question of time that these genes will get horizontally transferred.

The moment a new antibiotic is offered, the clock begins ticking — and the more it’s used, the sooner it becomes less effective. The goal is to create new drugs that are powerful against drug-resistant pathogens.

That’s why Polikanov’s research — and that of his colleagues, research professor Nora Vázquez-Laslop and distinguished professor Alexander Mankin, both in the Center for Biomolecular Sciences in the Retzky College of Pharmacy — is crucial. Both work on ways to attack bacterial cells’ ribosomes, molecular machines that work like 3D printers to produce proteins.

“Because the synthesis of proteins is crucial to life, if you stop it, the bacteria cannot live,” Polikanov says.

Human cells have ribosomes too, but they’re different enough from their bacterial counterparts that compounds can be developed to target bacterial ribosomes. This is a novel approach to crafting new antimicrobials academic researchers like Polikanov are free to pursue because they don’t have to consider the bottom line.

Along the way, they’re building a case for more investment in their approach. If they can provide ample evidence it works — and pinpoint specific compounds that will likely be effective — pharmaceutical companies will be more likely to step in and usher a new drug through FDA approval.

The CDC reports people who are Black and Hispanic are more likely to be diagnosed with late-stage cancers, making treatment more challenging and increasing the risk of death. In fact, Black women are 40% more likely to die from breast cancer than white women.

Enter Professor Debra Tonetti. By the time she joined the Retzky College of Pharmacy in 2001, she was already working to solve a major problem in cancer treatment. About three-fourths of women with breast cancer have a type that responds effectively to endocrine therapy, usually with the drugs tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors.

But for nearly half of these patients, these endocrine drugs eventually stop working. Their cancer becomes metastatic, meaning it spreads to other parts of their body. At that point, physicians have few choices outside of toxic chemotherapy.

Tonetti aimed to understand why this happens. She created mouse models of treatment-resistant breast cancer, exploring what made these tumors tick and how to shrink them. Once she had some basic ideas — including that, though estrogen fueled their growth, some forms of the hormone could also work against these cancers — she began exploring how to turn those ideas into new cancer drugs.

The next step was a crucial one. Tonetti walked down the hall to the lab of a colleague, Greg Thatcher, then a fellow member of the Cancer Center and the founding director of UICentre.

“My expertise is cancer biology; his is in medicinal chemistry,” Tonetti says. “You don’t get a drug unless you have both pieces together.”

Based on Tonetti’s findings, Thatcher tweaked molecules to engineer a new compound, which they tested and ultimately submitted in an investigational new drug application to the Food and Drug Administration, which granted them approval to conduct a Phase I clinical trial.

In Phase I trials, which are designed primarily to test drug safety, not efficacy, the results were more compelling than they could have hoped. In seven of the 15 patients enrolled, their compound halted disease progression; in two of them, this stabilization period lasted 10 months.

“Hearing that their quality of life was turned around — that was very gratifying to see,” Tonetti says.

Meanwhile, in the chemistry department, Cho has spent a nearly 30-year career studying lipids. These fatty compounds, including cholesterol, were once thought to primarily form cell membranes. But thanks to the work of researchers like Cho, it’s now clear they serve a wide variety of functions, including mediating the way cells respond to each other and their environment.

Cancer

The realization that his work could help dismantle health disparities — both inflammatory breast cancer and colorectal cancer are more common and more deadly among Black patients — has inspired Cho to continue forging ahead into brave new spaces.

— LAS Science Endowed Chair and Distinguished Professor of Chemical Biology Wonhwa Cho

While he was toiling away to determine exactly how lipids exert their effects, he and other cancer biologists recognized their crucial role in tumor development. So Cho found himself with an exciting and gratifying new direction for his work: developing life-saving treatments for cancer, a disease that will kill more than 600,000 Americans this year alone, with disproportionately more deaths among racial and ethnic minorities.

“Cancer uses many different tricks to survive and proliferate and metastasize, and many of these processes seem to critically depend on lipids,” he says. “If you block these lipid-mediated processes, you can suppress the growth of cancer cells, you can hinder their interaction with the immune system, you can block their way of developing resistance to drugs. You can basically eradicate cancer.”

Working with collaborators across UIC and beyond — including the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston — Cho and his lab have now identified several compounds that hold potential as cancer therapies, including potential drug candidates for colorectal cancer and inflammatory breast cancer.

The realization that his work could help dismantle health disparities — both inflammatory breast cancer and colorectal cancer are more common and more deadly among Black patients — has inspired Cho to continue forging ahead into brave new spaces.

The process of developing a new drug is long and arduous, but he and Tonetti are moving full steam ahead, building on UIC’s strong history in the field. Previous success stories include Prezista, a 2016-approved HIV drug discovered by researchers in the LAS’ Department of Chemistry that has helped transform the treatment of the disease; Shingrix, a shingles vaccine on the market since 2017 that originated in the College of Medicine; Tice BCG, a weakened live bacterium used to treat bladder cancer developed in the Retzky College of Pharmacy; and Phexxi, a nonhormonal contraceptive gel developed by faculty in the Retzky College of Pharmacy that the FDA approved in 2020.

Providing the Tools

Big ideas don’t become the pills or injections that change lives without cutting-edge technology and the coordination of the many steps necessary in drug development.

Fortunately, UIC offers support every step along the way, says Paul Carlier, Hans W. Vahlteich Chair in Medicinal Chemistry, professor of pharmaceutical sciences and chemistry, and the director of UICentre since 2022.

Once researchers like Tonetti or Cho identify a promising pathway, the next step is to determine if it’s possible to develop a drug that accomplishes what they hope. This stage is where tens or even hundreds of thousands of candidate molecules are tested to see if they might work.

From there, researchers might license the target drug to a pharmaceutical company, which UIC’s Office of Technology Management assists in. That company would then provide the significant resources required to advance the drug into clinical trials.

While those trials aren’t necessarily done at UIC, they can be — and in fact, many drug companies will bring compounds developed at other institutions here for testing due to the unique patient population. (In trials done through the Cancer Center, for example, 79% percent of the patients enrolled are Black or Hispanic.)

“UICentre is unique within Chicago with respect to the absolute scope and depth of drug discovery capabilities,” Carlier says. “Other institutions may offer pieces, but they don’t have the whole menu.”

Representation Matters

To truly impact health disparities, drug discovery must not only listen to the needs of communities but also include diverse populations in trials.

Not doing this would mean some people are unnecessarily barred from potentially life-saving treatments, and trial results are skewed because they don’t include people who are more susceptible to aggressive forms of cancer, Kitajewski says.

There are so many ways science can make better drugs by having diverse patients in clinical trials and an appreciation for all the features that make us different – our socioeconomic status, our nutrition, our genetics, our ability to get access to screenings and care.

— Jan Kitajewski, director of the University of Illinois Cancer Center and head of UIC’s Department of Physiology and Biophysics

Take, for example, the many Black people of sub-Saharan African descent who have a genetic variation that protects them from some types of malaria but also decreases levels of white blood cells called neutrophils. Because many cancer treatments also affect neutrophil levels, people with this variation, called the Duffy mutation, are often excluded from clinical trials.

Designing drugs that truly work for everyone is a moral imperative that demands an understanding of everything, from these genetic differences to how a person’s neighborhood influences their health.

“There are so many ways science can make better drugs by having diverse patients in clinical trials and an appreciation for all the features that make us different — our socioeconomic status, our nutrition, our genetics, our ability to get access to screenings and care,” says Kitajewski. “The science of the future will integrate all of those features to think about how patients should be best served.”

That’s where UIC truly shines. In addition to its underlying social justice mission and diverse faculty and student body, UIC’s community-to-bench model means input from patients and on-the-ground partnerships with community members shape both the direction of research and the implementation of its outcomes, says Lisa Freeman, dean of LAS.

The Retzky College of Pharmacy and College of Medicine house not only researchers working on the biological mechanisms of disease and the medicinal chemistry needed to develop drugs, but also clinicians working directly with patients.

“We have around 100 pharmacists who work in the clinics and the hospital, with physicians, helping treat patients with these medications,” says Glen Schumock, Herbert M. and Carol H. Retzky Dean of the College of Pharmacy. “They can see what’s not working with current drugs and give basic researchers ideas on how to better design the next generation of drugs. We can always provide feedback, in a kind of constant loop.”

Facilitating the Process

When Cho works with researchers from the College of Medicine or utilizes core facilities there, one of his lab members packs samples in dry ice and transports them across campus, about a mile trip. In the new DDCRP, with more collaborators under one roof, existing projects will move more quickly and smoothly.

Then, there are the serendipitous discoveries and partnerships that come from inhabiting the same space — that ability to do what Tonetti did years ago and stride down the hall to discuss a burning research question.

“When you bring people together who have different and complementary sets of expertise, the fact that you’re in the same building will lead to conversations that turn into ideas, which turn into projects that would have never happened had we continued to operate in our own separate spaces,” Carlier says.

That cross-pollination will also extend to community partners. Community members are involved at many levels in the Cancer Center and other research areas — they sit on advisory boards, review grants, weigh in on the design of clinical trials and contribute to advocacy work by joining faculty and staff to talk to state and national lawmakers.

“They do everything that we do short of putting on a lab coat and doing the experiments at the bench — and one day, maybe that will be part of what they do, too,” Kitajewski says.

Better Health for All

UIC’s mission is to provide the broadest access to the highest levels of educational, research and clinical excellence, an idea that resonates across the university, hospital and clinics.

For Reizine — and many others — treating patients and researching cures are not just a professional aspiration, they are deeply personal.

“Oncology is a hard field. I take care of metastatic patients, who ultimately succumb to their disease once we've run out of the therapies,” she says. “But what helps me is thinking of how these patients live on in the research and altruistically help others.”

It’s something that Allen, one of Reizine’s community advisory board members, noticed.

“When you talk to someone at the Cancer Center, you don’t feel like you’re talking to a scientist or doctor,” he says.

“You know you’re talking to a health care professional, but what you don’t expect is that personal commitment. You hear other people talking about doing things in the community, but here is an organization that’s actually doing it. That’s special.”

Dr. Natalie Reizine poses with Elverage Allen during his visit to the Vander Griend Lab at UIC. Reizine and Donald Vander Griend, associate professor in pathology and head of the prostate cancer laboratory, have both been guests on Allen’s podcast, “Prostate Cancer Real Talk.” Photo: Anthony Jackson

You can listen to Allen’s interviews with Reizine and Vander Griend on “Prostate Cancer Real Talk.”